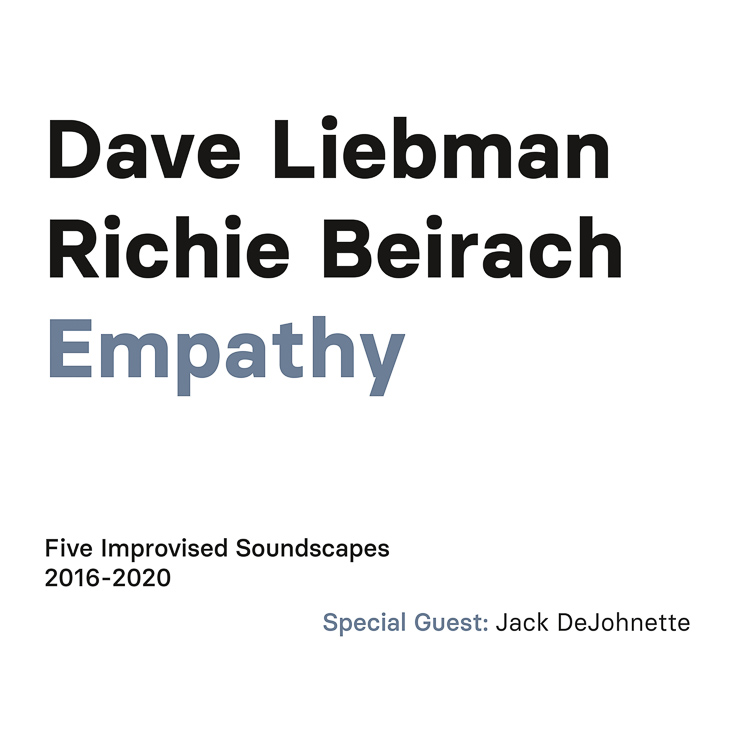

EMPATHY

Five Improvised Soundscapes 2016-2020

D 77094 (CD)

listen on AppleMusic or Spotify

description

Jazz, it is often said, is a community, a family of relationships, built on the strength of common experience. As the solidity of those relationships increase over time, the music matures and reflects that sense of mutuality—a palpable feeling of respect, dedication, and shared freedom resulting in performances of lasting freshness: conversations between like-minded souls. Yet jazz—especially in the modern era—is equally known for creative associations that do not last long, as the push for individual development rarely works in equal force or along parallel lines.

Think of it: Miles and Coltrane together? Less than 5 years. Bird and Max Roach? About as long. The shelf lives of almost all celebrated jazz pairings seem brief at best. Legendary bands too. Art Blakey had a dictum when he felt it was time for one Messenger or another to leave the nest. “This ain’t the Post Office!” he’d say in a raspy tone, urging them to the door before they got too comfortable. He wasn’t the only bandleader like that. As the circle of jazz draws together, so it drives them apart: shaking things up, keeping the music moving.

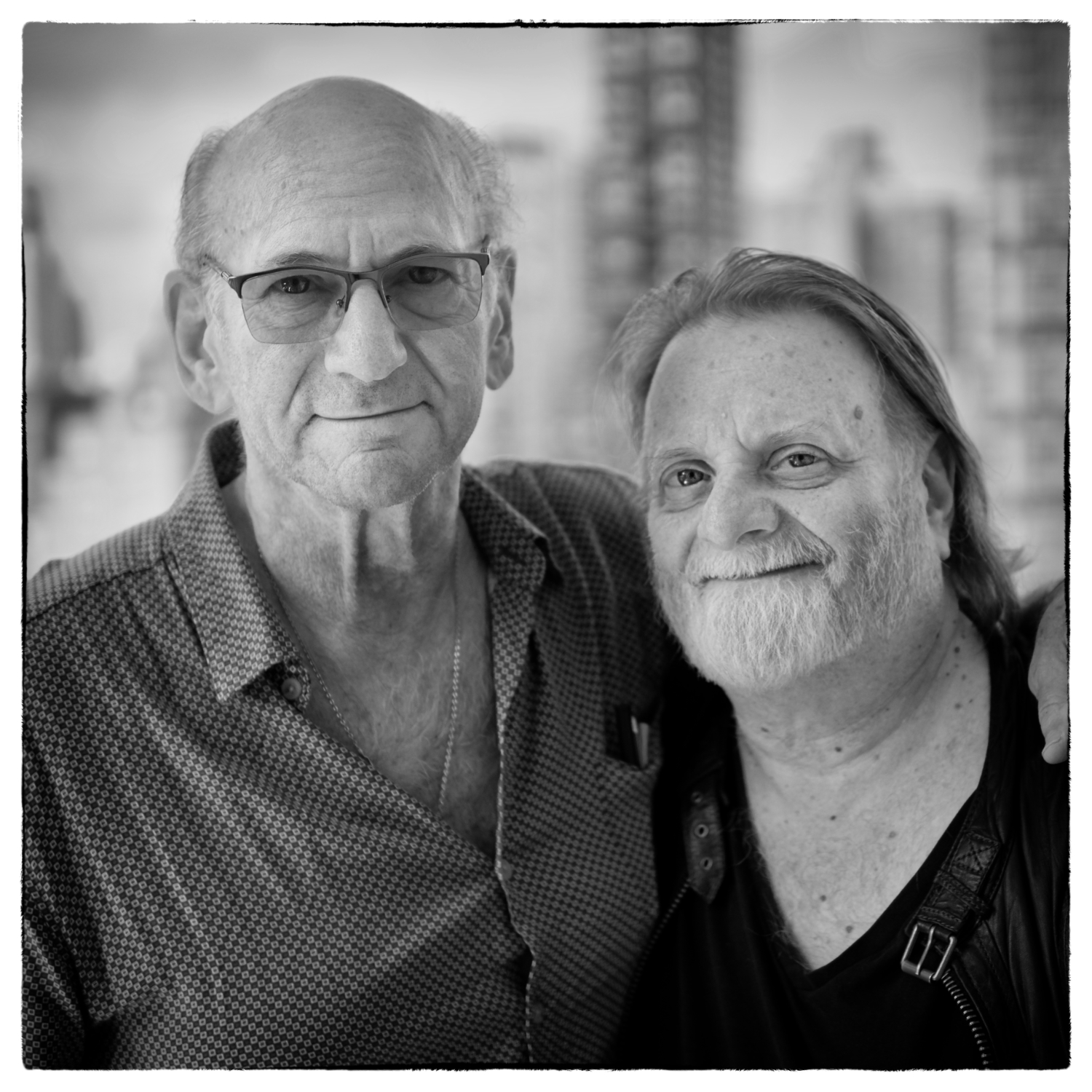

Richie Beirach and Dave Liebman are a jazz partnership born from this grand jazz tradition of finding musical comfort while avoiding stasis, of coming and going. There’s has been a creative, repeated pairing lasting for decades—on and off and then on again—and yielding recordings of depth and penetration every time they’ve met and made music together. Over the years, their musical approaches—individually, collectively—grew and developed, as they met and recorded repeatedly, in duets, groups they co-led, and guest appearances on each other’s albums. They’ve performed and toured and experienced life together. They’ve dedicated themselves to music education as well, teaching and formally and informally passing on what they have learned to newer generations of players. The catalogue of their musical encounters now stretches back over fifty years, and merits celebration and study—certainly more than it’s generally received in the past. It also defines a vigorously creative relationship filled with surprise and subtlety; and one that is clearly not over.

Let’s roll the story back to the beginning. Both Liebman (born 1946) and Beirach (1947) grew up in post-war Brooklyn, New York City, falling in love with music—and then jazz—when it was in its post-bop, golden-years period. They came of age in the early ‘60s, two teenagers discovering who they were and figuring out what they were supposed to do with their lives. Neither was born into music, growing up with music not so much around them, as available to them. Beirach’s initiation came early, discovering the piano as a five-year old and launching himself into lessons. For Liebman, it was the piano at first, but hearing John Coltrane perform “My Favorite Things” while on a junior high school date at Birdland, convinced him to apply himself to the saxophone.

Jazz quickly became their common obsession. They explored the music and musicians of the day, both as fans and players, peering in through that brief window—the late Fifties to the early Seventies—when players representing every jazz era were alive and active, from Armstrong to Ayler, from the legends of lore to a new generation of energy players. Jazz was the musical cutting edge of the culture then, almost singularly so, and it represented a social overlap as well—where black and white America met and mingled, jazz clubs representing a world away from the “world”—away from the day-to-day sting of racist reality—a space with a different set of rules, where society’s lines were less harshly defined. Black and white still mattered, and there was a new musical language to be learned and an education to be had that went deeper than just the music, if a young player was open and curious and wanting to grow. It was also a day when jazz schools and jazz educational programs were rare and the exception, not the rule.

Liebman and Beirach negotiated the jazz venues and woodshedded. They read instructional books on improvising (a limited library at the time), took one-on-one lessons from veteran players, and started to make the scene. In 1967, their paths first crossed at a Queens College jam session. Soon they were hanging out, listening and learning the music together, and eventually moved into Manhattan—Liebman to a loft on West 19th Street, Beirach to an apartment on Spring and Hudson Streets, across from the Half Note club. A life-long partnership was born.

Their paths in the ‘70s—together and apart—followed the traditional ladder-climb of sidemen gigs (Liebman with Elvin Jones, Miles Davis, and others, Beirach with the likes of Stan Getz and Chet Baker) and their own projects and bands; Lookout Farm, a quartet featured both plus guests, being a standout ensemble that led to groundbreaking albums for ECM. The two became sparkplugs in the jazz loft scene of the early ‘70s, when many venues were closing their doors. Their music ranged from more traditional postbop styles, to free jazz and rock-fueled fusion, reflecting the sound of their generation. Over the years, this multilinguistic range allowed them to explore different situations in the studio: acoustic and electric, small groups and larger ensembles. Quest, another quartet they co-led, at times featured bassists George Mraz or Ron McClure, and drummers Al Foster or Billy Hart. Repeatedly, Liebman and Beirach would meet and record as a duo, on albums like Forgotten Fantasies (1975), Omerta (1978), The Duo: Live (1985), Chant (1990), and Eternal Voices (2017).

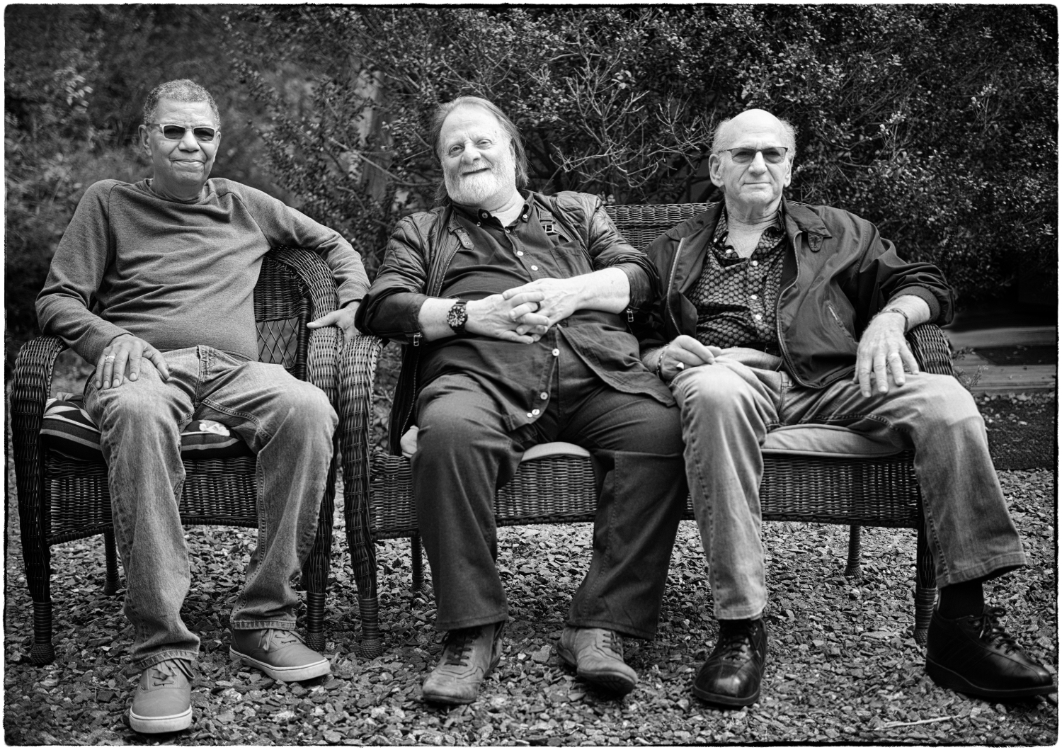

The circle, as the song goes, is unbroken. Empathy marks another significant step in the Liebman-Beirach timeline, and much more than that. It’s a five-disc outpouring of new music recorded in a four-year period in a variety of situations: a duo featuring Liebman and Beirach: Empathy. Trio with drummer Jack DeJohnette added: Lifelines. Liebman solo on saxophone—Aural Landscapes—and Beirach solo on piano: Heart of Darkness. The last disc is titled Aftermath: a 50-minute, ambient-jazz excursion involving reeds, flute, and keyboards performing over a percussion track prepared by veteran producer Kurt Renker who has known and worked with both musicians since the 1970s. DeJohnette’s participation merits further attention. While he now stands as a father figure in the realm of creative drumming, a major influence who came up as a member of the same generation as Liebman and Beirach, an older brother and fellow traveler in the world of improvised expression. Like them, he has maintained a sense of exuberance and discovery that belies his years (he was born in ’42.)

Beirach and Liebman share comment on the music, as does Renker, and it’s valuable reading. But I encourage checking out the music first. The path from one track to the next—and disc to disc—offers a marathon listen. I’ve done it a few times. The emotional effect of this music is wondrous and never less than warm and inviting: their choice of title for the collection is both evocative and accurate. So is the subtitle. “Improvised Soundscapes” describes this voluminous offering well.

Empathy is a cohesive balance of expansiveness and intricacy, a series of sonic worlds filled with starkly defined details, intimate moments of lightness and depth, surprises and side steps, and lots of space. Space in which to breathe and be curious and experience one’s own connection to the music. Space in which to hear the stories that come from more than fifty years of making music together.

—Ashley Kahn, January 2021

Ashley Kahn is author of A Love Supreme: The Story of John Coltrane’s Signature Album, and other titles on music.