Jazzline N 77027 (CD) / N 78027 (LP)

Jazzline N 77027 (CD) / N 78027 (LP)

ALSO AVAILABLE IN VINYL 180g DIRECT METAL MASTERING

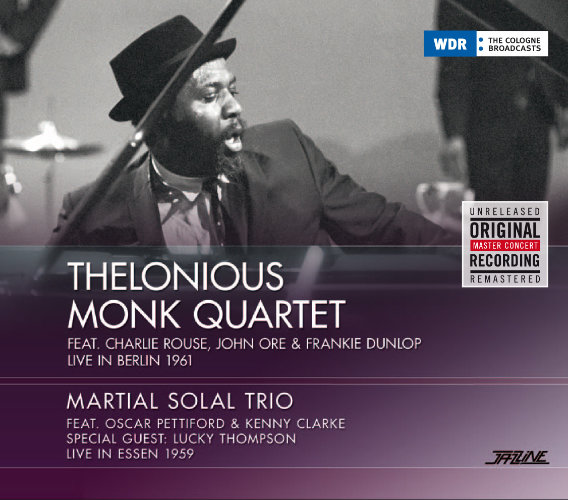

feat. Charlie Rouse, John Ore & Frankie Dunlop

LIVE IN BERLIN 1961

MARTIAL SOLAL TRIO

feat. Oscar Pettiford & Kenny Clarke

LIVE IN ESSEN 1959

description

Thelonious Monk and Martial Solal. At a first glance these two men have very little in common.

One of them seems to interrupt the swinging flow with bulky crossbars, allegedly an awkward bull in the china shop of jazz, bouncy and stumbling, a pianistic roughneck. Already his hand position prompts piano teachers to throw their hands up in horror: with the fingers stretched out flat and parallel, it seems as if two fly flaps were maltreating the keyboard. Before an aesthete even gets a chance to come to terms with this sight Monk’s lower arm crashes down on the ivory with a tremendous cluster.

The other man is an embodiment of the filigree. In the ears of his admirers his amazing virtuosity lets him catch up with the Piano-Olympus of a Tatum or Oscar Peterson, which is actually considered unreachable. A certain “Gallic humour” is attributed to Solal, a playful elegance, which is not lost in very suddenly interspersed harmonic turns. An orchestral density and an almost continual flow of bubbling ideas force the breathlessly following listener to occasionally gasp for air.

In the USA and France the most renowned competitions of both countries are named in their honour (Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition, Concours de piano jazz Martial Solal). While the Frenchmen was acclaimed already very early in his career and was turned into a sort of “embodiment” of Gallic jazz, Monk’s relevance – particularly as a composer – was only completely appreciated after his death. His wish to be understood by the audience only came true towards the end of his career – if at all. Most of the time he felt misinterpreted. And even Solal at times quarrelled with his contemporaries: “too complex” was an often uttered reproach, which he usually retorted by referring to the “lack of knowledge” of the jazz audience.

Reflections, twists, the concatenation of seemingly not matching parts, the sudden compression and thinning of fundamental chords: While Solal is a form-conscious designer, nimbly treating the individual elements, Monk creates sometimes seemingly bizarre but surprisingly stable constructs, which make him an “architect of highest repute” in the words of Coltrane (constructs, which Charlie Rouse managed to deal with way better than any other saxophonist). Above all one thing joins them together: Both were uncompromising individualists and one could accuse them of many things but certainly not of being indifferent. Especially the American polarised. In June 1961 Dieter Zimmerle described in the Jazz Podium magazine to what extent the pianist divided his audience – in supporters and opponents:

“To be on Monk’s side or to be not on his side was the question after what was certainly the most impressing concert at the Deutscher Jazz-Salon Berlin. Rarely a jazz group was met with such unfettered approval and simultaneously with such brusque rejection as the Monk-Quartet…The quartet is one of these groups, which despite the fundamental conception of the music, broadly ignore the formal laws of musical tradition to never loose the element of fascination caused by a deliberate or unconscious shock…In doing so, the shock is triggered by the individual musicians in different ways: in the case of Monk by his almost hostile treatment of the piano, Charlie Rouse releases it by impetuous outbursts in tenor and Frankie Dunlop by rhythmic escapades, which he is able to perform thanks to his outstanding playing technique. But despite all that the quartet – John Ore tries to mediate with his unswerving basso – comes across as a well organised and self-contained unit, which one may only like or dislike in total.“

Another guest at the Jazz-Salon was Monk’s ten year younger French colleague, who in Zimmerle’s words “showed such an outstanding technical brilliance which already threatened the persuasive power of jazz”.

While Solal performed together with the European All Stars at Berlin he had already played the West-German audience into a state of dizziness all alone two years earlier – highly motivated as the pianists performing before him at the Grugahalle had set the standards extremely high: Oscar Peterson as a member of the Jazz at the Philharmonic guaranteed a celebrated opening of the Essener Jazztage 1959 in front of an audience of 8200 people. The second part of the first evening was performed by the Albert Mangelsdorff Jazztet, Clara Ward & The Ward Singers and the Martial Solal Trio. Oscar Pettiford and the Parisian-by-choice Kenny Clarke formed the rhythm section which performed even twice on the following and concluding day of the festival: together with Bud Powell and Rolf Kühn. As a guest, Solal presented the saxophonist Lucky Thompson who had come to Paris in 1957 and who can be heard in two numbers on the soprano saxophone (which was particularly popular in France in these days).

In their book Blue Monk the Monk-biographers Jacques Ponzio and Francois Postif quote the producer and critic Louis-Victor Mialy, who in 1964 – when both pianists appeared within spitting distance of each other in San Francisco – tried to arrange a meeting of the two protagonists:

“Martial had asked me the delicate favour to get Monk to the El Matador. One evening, the club was packed with musicians who had come to hear Solal, I spotted Monk in a white suit and a white hat. Without even glancing at the stage to see who was performing, Monk directly headed for the bar, took off his hat and both of us ordered a double cognac. At the same time Solal was performing a firework on stage, added a little bit a Chopin and a lot of Tatum to his interpretation, which turned out to be particularly intense. Monk was still standing with his back to the stage, listened attentively and was starring a hole in the bar. Finally he turned round and asked me:’Who is this motherfucker?’ After finishing his double cognac Monk left the club like an English army officer with his head held high and without a word.”

Karsten Mützelfeldt