Jazzline N 77041 (2CD) / N 78041 (2LP)

Jazzline N 77041 (2CD) / N 78041 (2LP)

ALSO AVAILABLE IN VINYL 180g DIRECT METAL MASTERING

description

Audio-Lesson

When the band of a percussionist conquers the concert stages, then an emancipation of a particular kind is always part of the story. Although, from time to time a representative of this most primordial of all forms of music has made it to the top of an orchestra, like Chick Webb, the legendary discoverer and mentor of Ella Fitzgerald – until the studio- and recording technology was able to fine-tune the drums, the central role of the rhythmist was always constrained. The label of a “vassal of rhythm” showed the limited level of appreciation in reality, even in the world of jazz, despite the level of importance musicians like George Wettling or Zutty Singleton might have had in the old days of jazz.

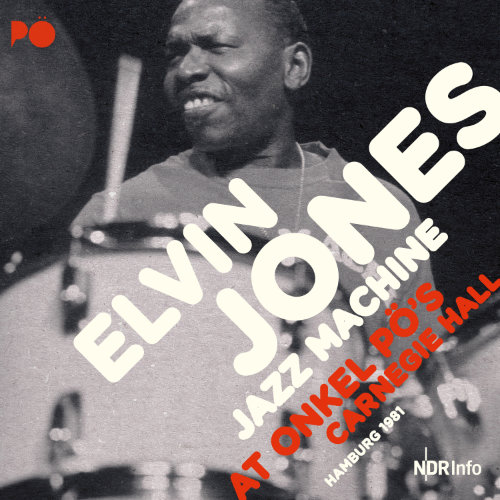

The liberation of the instrument most probably only started in earnest with Gene Kupa – but even his subtle and vibrant performance in Benny Goodman’s orchestra at the legendary Carnegie-Hall-Concert of January 1938 is more a matter of guessing than hearing on the recording of this history-charged event. However, from then on the road fairly quickly led to the style-defining masters, the sorcerers and magicians at the drums: amongst many others, Buddy Rich and Max Roach, Kenny Clarke and Art Blakey, Mel Lewis – and of particular importance for us - Elvin Jones. He brought an exceptional sextet to “Onkel Pö’s Carnegie Hall” on Lehmweg in Hamburg-Eppendorf in September 1981. Also this concert is documented in full-length and in all its relaxed beauty on this record.

Elvin Ray Jones was born in Pontiac in 1927 as the youngest of ten children and brother of pianist Hank and trumpeter Thad Jones. In 1981 his formative years were long gone – about one and a half decades earlier the percussionist had left the quartet of charismatic saxophonist John Coltrane, after having been part of it for five years; Elvin Jones was involved in milestone-productions such as “A Love Supreme”. Already during and especially after his time with Coltrane, the percussionist enriched various modern jazz ensembles; for instance, he attended the German jazz festival at Frankfurt in 1978 as a member of the European-American formation “Concert Jazz Band” of the Swiss pianist, arranger and composer George Gruntz.

Elvis Jones was always one of those drummers who are comfortable to occupy centre stage: a powerful package of energy and inspiration; treating the instruments in a rather rough way but nevertheless with delicate structures in his own performance. Already the duration and sequence of the pieces of this Hamburg recording are proof of his enormous self-confidence - Jones really had a lot of staying power; hardly any of the themes he selected for the concert lasted less than twenty minutes. Ever since the epoch of hard bop this relaxed attitude, overrunning all previous limits, came out on top – musicians now “told stories” on their instruments as long as there was anything to tell; and sometimes even a little bit longer.

Elvin Jones called his own ensemble “Jazz Machine”; the name was not due to a somewhat mechanical and cold sound of the drums – on the contrary. The orchestration of this “machine” was rather unconventional – Jones had invited two tenor-saxophonists, Carter Jefferson (who passed away already in the mid-90s) and Dwayne Armstrong; also in this way he cemented the staggering sound of the group. Opposite of the bugles performed, surprisingly enough, the guitarist Marvin Horne; and with the Japanese pianist Fumio Karashima the Jones-“Machine” had at its command a particularly non-mechanical melodist, especially when it concerned the ballads; in this case “In a sentimental mood” and “My one and only love”. Karashima also added a noteworthy dosage of far-east melodics and harmony to the concert. Together with Karashima and the well-tried bassist Andy McCloud, Elvin Jones had recorded a trio-LP just previously to the European tour documented here.

The material for the recording from “Onkel Pö” feeds on concise themes and motives from all established sources of the hard bop era; often and readily the blues elements prevail. Right in the middle of it all Elvin Jones proves his mastery again and again– even after more than three decades(and long after Elvin Jones passing away in 2004) his performance remains an object-lesson, or better: an audio-lesson for everybody, who is looking for orientation and guidance through the history of the emancipation of the drums in jazz; until today.

Michael Laages