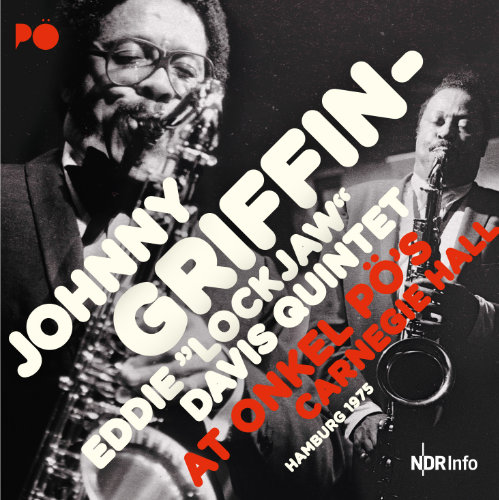

Jazzline N 77046 (2CD) / N 78046 (2LP)

ALSO AVAILABLE IN VINYL 180g DIRECT METAL MASTERING

description

The “Ever More” of Jazz

One of the most fascinating chapters in jazz history has been written by the “Americans in Europe” – masters of jazz from the homeland of this genre of music, who for different reasons did not feel at ease in their fatherland, the USA; most of the time there were just not enough jobs and even less appreciation for their work. The latent racism also played a role and some wanted to protest against the hubris of their home country, which wanted to police the world and again and again stumbled into armed conflicts. Furthermore, already in the 50s some big bands disintegrated while being on tour in the “Old World” – and Paris, London, Stockholm or Copenhagen – in some rarer cases also Berlin, Munich or Frankfurt – became a new home for high-profile jazz stars.

Johnny Griffin, born in Chicago in 1928, was one of them. When he appeared on stage at “Onkel Pö’s Carnegie Hall” on Lehmweg in Hamburg-Eppendorf on 8 August 1975 as the leader of an illustrious quintet, he had just settled in the Netherlands for a while. However, he also called London, Paris and Stockholm his home at times; especially in Paris he did splendid work as a member of the big band of Kenny Clarke and Francy Boland. Also in Peter Herbolzheimer’s Rhythm Combination & Bass he made a strong impact and in the same year as the Hamburg concert took place, he was a guest in Klaus Doldinger’s band. After a brief return to the USA in the 70s, John Arnold Griffin III spent almost a quarter of a century in the rural setting of the French department of Vienne, until he passed away at the age of 80 in 2008. Up to a ripe old age he went on concert tours from this home base.

The band from the summer of 1975 was quite exceptional: Art Taylor displayed fireworks on the drums, Niels-Henning Örsted-Pedersen from Copenhagen, for a long time Europe’s most important bassist, was part of the team, the Spanish pianist Tete Montoliu also joined in (who had quite a hard time to compete technically with his high-power colleagues). Furthermore, alongside Griffin also performed Eddie Davis, whose nickname “Lockjaw” gives an idea of his staying power on the saxophone. Also Griffin showed a lot of endurance – when he started a solo, one never knew for how long it would last and when (if ever) he would come to a close. Johnny Griffin was and remains the uncrowned king of the “never-ending stories“; uncountable were the musical citations he was able to include in his untamed monologues on the saxophone. Perhaps, sometimes he might have intended to tell the entire history of jazz all on his own. In any case, many were indeed introduced to the history of jazz by this physically small man with almost unlimited resources of energy.

Already as a teenager Griffin was part of Rhythm ‘n’ Blues bands and found friends for life there, for instance Percy Heath and Philly Joe Jones; he even accompanied singers such as Ella Fitzgerald or Betty Carter. Back then his instrument was the alto saxophone. He appreciated Johnny Hodges and also focused on ballades by Ben Webster. However, in Lionel Hampton’s orchestra he switched to the tenor saxophone in 1946. Very soon afterwards the young mister Griffin got bitten by the bug of the bebop-revolution, which changed so much in the world of jazz.

The first recording under his own name was released in 1956 and four years later he was together with “Lockjaw”-Davis in a rather successful and popular band. In this respect the concert in Hamburg fifteen years later was also a sort of revival. When Davis starts off the second part of the NDR-recording with the master-standard “I can’t started“, followed by “Stompin‘ at the Savoy“ with Griffin and Davis alternating, then it becomes clear what these two musicians appreciated in each other: the partnership in the creative rivalry and cooperation of their voices. Pleasantly and with a lot of air Davis filled the room with sound, crisp and robust was Griffin’s reaction. Together they were almost unbeatable.

Furthermore, the “Pö”-concert was a typical Griffin-evening. “Little Giant” (as the community called him) was never really interested in a clear structure – the pure energy of exuberant storytelling was his element. With one small motive (e.g. “Funky Fluke” towards the finale) he could easily fill one side of an LP; he always had something more to tell. This was in a way the motto of these seemingly never-ending story: always give more, always find more. Everything Johnny Griffin found, he willingly shared with us in his stories.

Also because of this attitude the audience at “Onkel Pö” in Hamburg on 8 August was once more in an enthusiastic mood. The heart of jazz was beating strongly.

Michael Laages